When the Village of Corona joined the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources’ Healy Collaborative Groundwater Monitoring Network in 2017, they began receiving depth to water measurements collected in the middle of the day and the middle of the night in their municipal supply well. Who could need so much data? What use could it be?

Now, almost six years later, as the village contemplates its water future, the collected measurements provide crucial support in the decision-making process.

Windfarm construction is coming through and it takes a lot of water.

Specifically, as much as 36 gallons of water per yard of concrete batched for wind turbine foundations, or approximately 21,600 gallons of water per wind turbine foundation (Magic Valley Energy LLC, 2021). Then there is additional water use for road construction, dust control, and construction personnel consumption.

The conundrum the village faces is one of water resources versus monetary resources. Should Corona sell water for construction and bank that revenue for projects to improve town infrastructure? Or should the village save groundwater for residential use only, and lose the potential to generate needed revenue?

“I can see both sides of the picture,” says village Clerk and Treasurer Terri Racher. Some town residents say the water should be saved for residential consumption, while others say the town should sell water to generate revenue. “A broad spectrum of opinions and a very fine line to walk,” remarks Racher.

The water data collected by the Healy Collaborative Groundwater Monitoring Network can hopefully provide some clarity to assist in the decision-making process.

The Village of Corona relies on two supply wells located in Cibola National Forest about 12 miles from the village. With very few private wells in the region, the town’s ranching community of 165 residents relies on the village system for their water resources.

One of the Corona supply wells is equipped with an acoustic data logger, a device that sits atop the well. The acoustic device sends a pulse of sound down the well that bounces off the water surface and travels back up to a microphone. The device records the time it takes for the sound to travel down to the water and back, and translates this time to a depth-to-water measurement in feet below the ground surface.

“[It’s] being able to see on a daily basis our static water levels and compare that to how much water we are actually pumping out and how much we are using,” says Racher. “How does [the pumping] directly affect those static water levels? If we’re seeing a big draw down, are those wells recovering quickly or is that static water level dropping?”

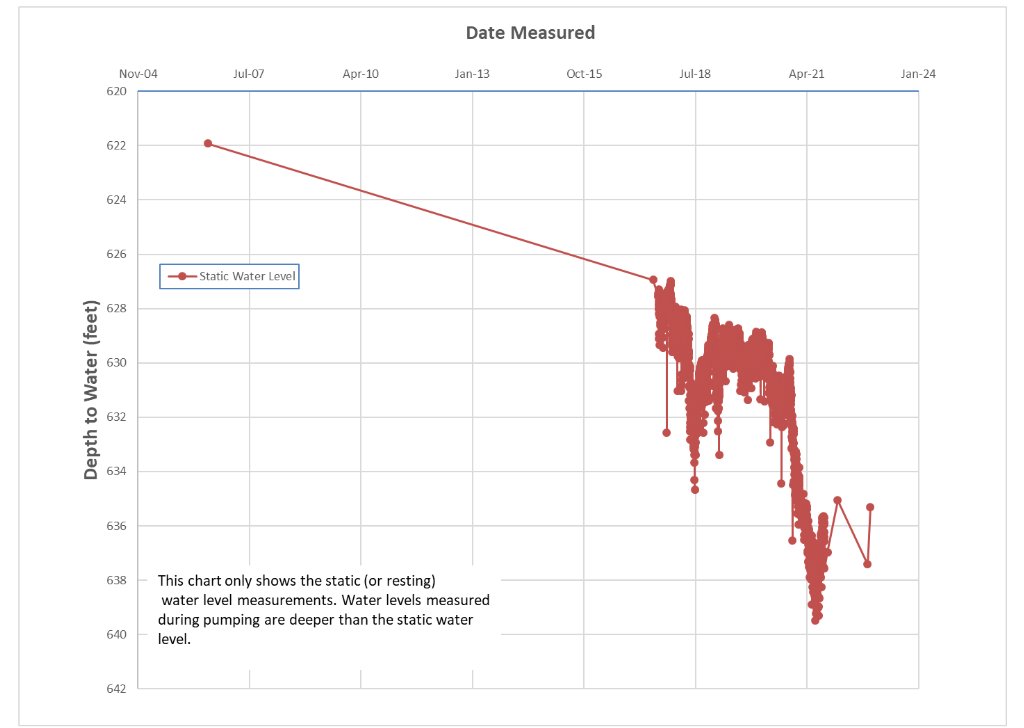

The measurement most useful for monitoring aquifer health is the static water level. When a well pumps water, it draws down the water level. When the pump shuts off, the water level returns to a height that corresponds to the level of the local aquifer. This is the static water level.

If we want to monitor the health of our aquifers, we have to keep an eye on their static water levels. Over time, the static water level measured in a well can decline. A clear sign of trouble, this indicates that the aquifer is out of balance and more water is being pumped from the ground than is being recharged through surface water infiltration.

Eventually, extracting more water than is being recharged leads to aquifer decline, often termed ‘groundwater mining.’ Groundwater is a finite resource, and as water levels drop, it becomes more expensive to pump what remains and wells may go dry.

Measuring water levels in wells provides an important way to monitor if aquifers are declining. The mission of the Healy Collaborative Groundwater Monitoring Network is to work with communities like the Village of Corona to provide monitoring for their groundwater resources.

As a network participant, a staff member from the New Mexico Bureau of Geology visits Corona once a year to download data collected by the acoustic data logger. They also collect a manual depth-to-water measurement using an e-probe, a device attached to the end of a measuring tape that lets out a high-pitched beep when it reaches the water level in a well. This manual measurement helps validate the measurements collected by the acoustic data logger.

Data collected is then made available to Corona and the public via an interactive web map on the Bureau’s website. Looking at water levels over time can help indicate whether aquifers are declining.

“There are a lot of municipalities that have no idea what’s really going on underground,” says Racher, “and I think we’re very lucky to be able to see that and, at this point, in real time data. As a water poor state, that’s something that I think is very important.”

Back to the question at hand, should Corona sell water for windfarm construction? The Healy Collaborative Groundwater Monitoring Network can’t answer this thorny question, but it can provide data to help the town monitor its water resources and make an informed decision.

“I think that we have enough data that we can comfortably make some decisions about how much water we can sell without having a detrimental effect to our water system as a whole and I think we can safely defend our decision because we have the data to back it up,” says Racher. “I think we’re almost to that point where we can find that balance between bringing in the revenue and conserving our resources.”

For more information about the Healy Collaborative Groundwater Monitoring Network, please send an email to nmbg-waterlevels@nmt.edu or visit our webpage at geoinfo.nmt.edu/resources/water/cgmn/

Depth to water in the Corona well from 2007 through 2023. The static water level, showing the elevation of the water table when there is no active pumping, has decreased approximately 15 feet during the monitoring.