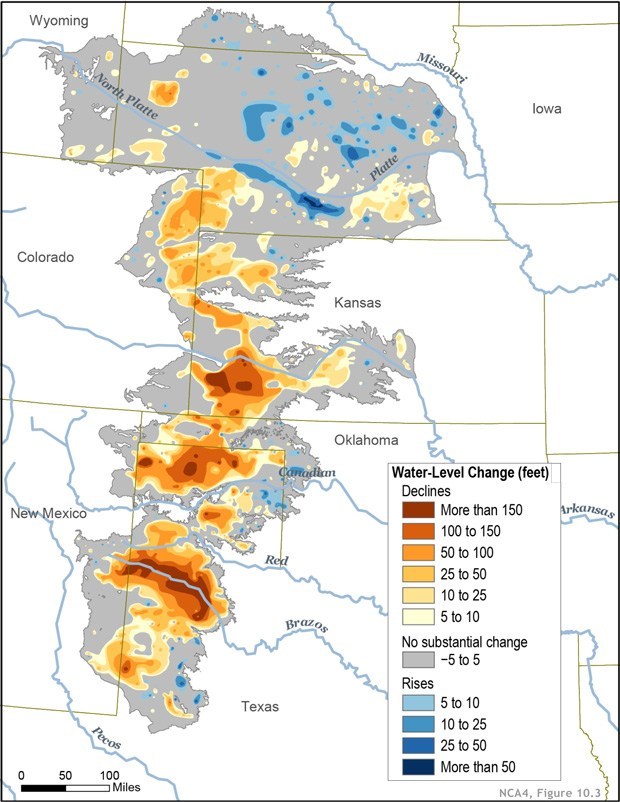

The Ogallala aquifer is rapidly declining.

The large underground reservoir stretches from Wyoming and the Dakotas to New Mexico, with segments crossing key farmland in Texas, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma. It serves as the main water source for what’s known as the breadbasket of America — an area that contributes at least a fifth of the total annual agricultural harvest in the United States.

The U.S. Geological Survey began warning about the aquifer’s depletion in the 1960s, though the severity of the issue seems to have only recently hit the mainstream. Farmers in places like Kansas are now grappling with the reality of dried up wells.

The Ogallala aquifer, also referred to as the High Plains aquifer. Source: U.S. Geologic Survey: McGuire, V.L., 2017, Water-level and recoverable water in storage changes, High Plains aquifer, predevelopment to 2015 and 2013–15: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5040, 14 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175040

In New Mexico, the situation is more dire. The portions of the aquifer in eastern New Mexico are shallower than in other agricultural zones, and the water supply is running low.

In 2016, the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources sent a team to Curry and Roosevelt counties to evaluate the lifespan of the aquifer. The news was not good. Researchers determined some areas of aquifer had just three to five years left before it would run dry given the current usage levels, potentially leaving thousands of residents and farmers without any local water source.

The news left local decision-makers in the region weighing options to balance farmland demand for irrigation and community needs for drinking water while a more permanent solution is put into place.

“There’s no policy in place to provide for that scenario,” David Landsford, who is currently mayor of Clovis and chairman of the Eastern New Mexico Water Utility Authority told NM Political Report.

Climate researchers and hydrogeologists agree these types of water scarcity issues will likely become more commonplace in the southwest and beyond as the climate further warms.

“Climate change, especially in the west and southwest, is already impacting us,” said Stacy Timmons, associate director of hydrogeology programs at the Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, at a National Ground Water Association conference in Albuquerque.

“There’s some places where we’re seeing some pretty remarkable declines in water availability that are, in some ways, reflecting climate change,” Timmons said. “You can see, just over the last twenty years, there’s been some pretty significant drought impacts to New Mexico, specifically.”

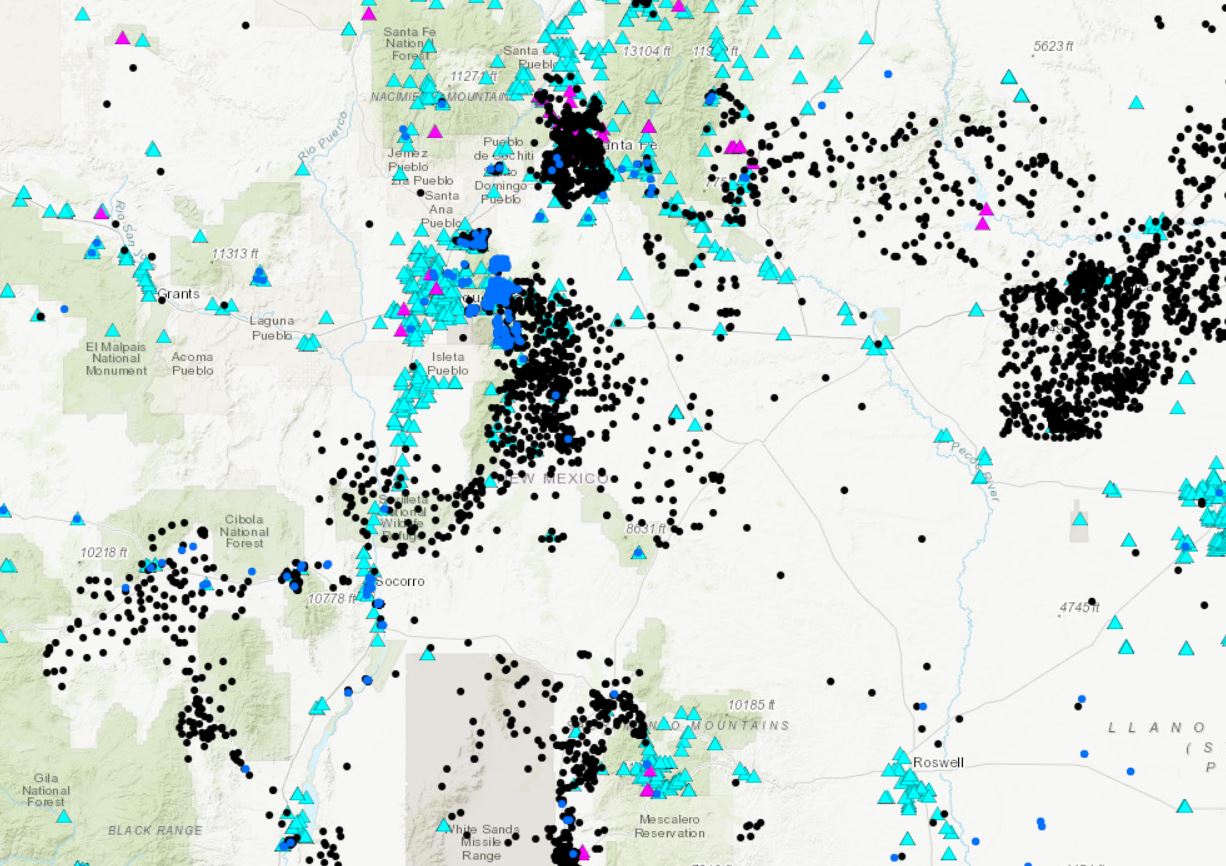

Timmons has assembled a team to head up a new initiative to help the state better track water use, quality and scarcity. The program revolves around data: aggregating all the water data that’s collected across different sectors, government agencies and research organizations in the state. The idea is that by collecting that data in one central location and making it available to everyone, policy makers will have a better understanding not only of current water resources, but also how to shape water management policies moving forward to reflect that reality.

“There’s a huge shift globally and nationally in how we’re looking at water,” Timmons said. “Here in New Mexico, we are really on the cutting edge of actually accessing some of this technology, and we’re starting to modernize how we manage our water and our water data.”